From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Pandemic H1N1/09 Influenza | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

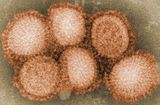

Electron microscope image of the reassorted H1N1 influenza virus. The viruses are ~100 nanometres in diameter.[1]

|

|

| MedlinePlus | 007421 |

| eMedicine | article/1673658 |

| MeSH | D053118 |

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Vaccines |

| Treatment |

| Pandemics |

|

| Outbreaks |

| See also |

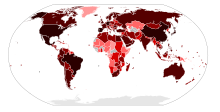

Initially coined an "outbreak", the stint began in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, with evidence that there had been an ongoing epidemic for months before it was officially recognized as such.[9] The Mexican government closed most of Mexico City's public and private facilities in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus; however, it continued to spread globally, and clinics in some areas were overwhelmed by infected people. In June, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. CDC stopped counting cases and declared the outbreak a pandemic.[10]

The onset of the pandemic coincided with a severe financial crisis triggered by the bursting of the US housing bubble, which has been compared in its severity to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Both events (pandemic and financial crisis) became entangled.[11]

Despite being informally called "swine flu", the H1N1 flu virus cannot be spread by eating pork or pork products;[12][13] similar to other influenza viruses, it is typically contracted by person to person transmission through respiratory droplets.[14] Symptoms usually last 4–6 days.[15] Antivirals (oseltamivir or zanamivir) were recommended for those with more severe symptoms or those in an at-risk group.[16]

The pandemic began to taper off in November 2009,[17] and by May 2010, the number of cases was in steep decline.[18][19][20][21] On 10 August 2010, the Director-General of the WHO, Margaret Chan, announced the end of the H1N1 pandemic,[22] and announced that the H1N1 influenza event has moved into the post-pandemic period.[23] According to the latest WHO statistics (July 2010), the virus has killed more than 18,000 people since it appeared in April 2009, however they state that the total mortality (including deaths unconfirmed or unreported) from the H1N1 strain is "unquestionably higher".[18][24] Critics claimed the WHO had exaggerated the danger, spreading "fear and confusion" rather than "immediate information".[25] The WHO began an investigation to determine[26] whether it had "frightened people unnecessarily".[27] A flu followup study done in September 2010, found that "the risk of most serious complications was not elevated in adults or children."[28] In an 5 August 2011 PLoS ONE article, researchers estimated that the 2009 H1N1 global infection rate was 11% to 21%, lower than what was previously expected.[29] However, by 2012, research showed that as many as 579,000 people could have been killed by the disease, as only those fatalities confirmed by laboratory testing were included in the original number, and meant that many of those without access to health facilities went uncounted. The majority of these deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia. Experts, including the WHO, have agreed that an estimated 284,500 people were killed by the disease, much higher than the initial death toll.[30][31][32]

Contents

Classification

Further information: Pandemic H1N1/09 virus: Nomenclature

The initial outbreak was called the "H1N1 influenza", or "Swine Flu" by American media. It is called pandemic H1N1/09 virus by the WHO,[33] while the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention refer to it as "novel influenza A (H1N1)" or "2009 H1N1 flu".[34] In the Netherlands, it was originally called "Pig Flu", but is now called "New Influenza A (H1N1)" by the national health institute, although the media and general population use the name "Mexican Flu". South Korea and Israel briefly considered calling it the "Mexican virus".[35] Later, the South Korean press used "SI", short for "swine influenza". Taiwan suggested the names "H1N1 flu" or "new flu", which most local media adopted.[36] The World Organization for Animal Health proposed the name "North American influenza".[37] The European Commission adopted the term "novel flu virus".[38]Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of H1N1 flu are similar to those of other influenzas, and may include fever, cough (typically a "dry cough"), headache, muscle or joint pain, sore throat, chills, fatigue, and runny nose. Diarrhea, vomiting, and neurological problems have also been reported in some cases.[39][40] People at higher risk of serious complications include those aged over 65, children younger than 5, children with neurodevelopmental conditions, pregnant women (especially during the third trimester),[5][41] and those of any age with underlying medical conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, or a weakened immune system (e.g., taking immunosuppressive medications or infected with HIV).[42] More than 70% of hospitalizations in the U.S. have been people with such underlying conditions, according to the CDC.[43]In September 2009, the CDC reported that the H1N1 flu "seems to be taking a heavier toll among chronically ill children than the seasonal flu usually does."[8] Through 8 August 2009, the CDC had received 36 reports of paediatric deaths with associated influenza symptoms and laboratory-confirmed pandemic H1N1 from state and local health authorities within the United States, with 22 of these children having neurodevelopmental conditions such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or developmental delays.[44] "Children with nerve and muscle problems may be at especially high risk for complications because they cannot cough hard enough to clear their airways".[8] From 26 April 2009, to 13 February 2010, the CDC had received reports of the deaths of 277 children with laboratory-confirmed 2009 influenza A (H1N1) within the United States.[45]

Symptoms in severe cases

The World Health Organization reports that the clinical picture in severe cases is strikingly different from the disease pattern seen during epidemics of seasonal influenza. While people with certain underlying medical conditions are known to be at increased risk, many severe cases occur in previously healthy people. In severe cases, patients generally begin to deteriorate around three to five days after symptom onset. Deterioration is rapid, with many patients progressing to respiratory failure within 24 hours, requiring immediate admission to an intensive care unit. Upon admission, most patients need immediate respiratory support with mechanical ventilation.[46]A November 2009 CDC recommendation stated that the following constitute "emergency warning signs" and advised seeking immediate care if a person experiences any one of these signs:[47]

- In adults:

-

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Pain or pressure in the chest or abdomen

- Sudden dizziness

- Confusion

- Severe or persistent vomiting

- Low temperature

- In children:

-

- Fast breathing or working hard to breathe

- Bluish skin color

- Not drinking enough fluids

- Not waking up or not interacting

- Being so irritable that the child does not want to be held

- Flu-like symptoms which improve but then return with fever and worse cough

- Fever with a rash

- Being unable to eat

- Having no tears when crying

Complications

Most complications have occurred among previously healthy individuals, with obesity and respiratory disease as the strongest risk factors. Pulmonary complications are common. Primary influenza pneumonia occurs most commonly in adults and may progress rapidly to acute lung injury requiring mechanical ventilation. Secondary bacterial infection is more common in children. Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant strains, is an important cause of secondary bacterial pneumonia with a high mortality rate. Neuromuscular and cardiac complications are unusual but may occur.[49]A United Kingdom investigation of risk factors for hospitalisation and poor outcome with pandemic A/H1N1 influenza looked at 631 patients from 55 hospitals admitted with confirmed infection from May through September 2009. 13% were admitted to a high dependency or intensive care unit and 5% died; 36% were aged <16 years and 5% were aged ≥65 years. Non-white and pregnant patients were over-represented. 45% of patients had at least one underlying condition, mainly asthma, and 13% received antiviral drugs before admission. Of 349 with documented chest x-rays on admission, 29% had evidence of pneumonia, but bacterial co-infection was uncommon. Multivariate analyses showed that physician-recorded obesity on admission and pulmonary conditions other than asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were associated with a severe outcome, as were radiologically confirmed pneumonia and a raised C-reactive protein (CRP) level (≥100 mg/l). 59% of all in-hospital deaths occurred in previously healthy people.[50]

Fulminant (sudden-onset) myocarditis has been linked to infection with H1N1, with at least four cases of myocarditis confirmed in patients also infected with A/H1N1. Three out of the four cases of H1N1-associated myocarditis were classified as fulminant, and one of the patients died.[51] Also, there appears to be a link between severe A/H1N1 influenza infection and pulmonary embolism. In one report, five out of 14 patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe A/H1N1 infection were found to have pulmonary emboli.[52]

An article published in JAMA in September 2010[53] challenged previous reports and stated that children infected in the 2009 flu pandemic were no more likely to be hospitalised with complications or get pneumonia than those who catch seasonal strains. Researchers found that about 1.5% of children with the H1N1 swine flu strain were hospitalised within 30 days, compared with 3.7% of those sick with a seasonal strain of H1N1 and 3.1% with an H3N2 virus.[28]

Diagnosis

Confirmed diagnosis of pandemic H1N1 flu requires testing of a nasopharyngeal, nasal or oropharyngeal tissue swab from the patient.[54] Real-time RT-PCR is the recommended test as others are unable to differentiate between pandemic H1N1 and regular seasonal flu.[54] However, most people with flu symptoms do not need a test for pandemic H1N1 flu specifically, because the test results usually do not affect the recommended course of treatment.[55] The U.S. CDC recommend testing only for people who are hospitalised with suspected flu, pregnant women and people with weakened immune systems.[55] For the mere diagnosis of influenza and not pandemic H1N1 flu specifically, more widely available tests include rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDT), which yield results in about 30 minutes, and direct and indirect immunofluorescence assays (DFA and IFA), which take 2–4 hours.[56] Due to the high rate of RIDT false negatives, the CDC advises that patients with illnesses compatible with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection but with negative RIDT results should be treated empirically based on the level of clinical suspicion, underlying medical conditions, severity of illness and risk for complications, and if a more definitive determination of infection with influenza virus is required, testing with rRT-PCR or virus isolation should be performed.[57] Dr. Rhonda Medows of the Georgia Department of Community Health states that the rapid tests are incorrect anywhere from 30% to 90% of the time and warns doctors in her state not to use them because they are wrong so often.[58] The use of RIDTs has also been questioned by researcher Paul Schreckenberger of the Loyola University Health System, who suggests that rapid tests may actually pose a dangerous public health risk.[59] Dr. Nikki Shindo of the WHO has expressed regret at reports of treatment being delayed by waiting for H1N1 test results and suggests, "[D]octors should not wait for the laboratory confirmation but make diagnosis based on clinical and epidemiological backgrounds and start treatment early".[60]On 22 June 2010, the CDC announced a new test called the "CDC Influenza 2009 A (H1N1)pdm Real-Time RT-PCR Panel (IVD)". It uses a molecular biology technique to detect influenza A viruses and specifically the 2009 H1N1 virus. The new test will replace the previous real-time RT-PCR diagnostic test used during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which received an emergency use authorisation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in April 2009. Tests results are available in four hours and are 96% accurate.[61]

Virus characteristics

Main article: Pandemic H1N1/09 virus

The virus was found to be a novel strain of influenza for which extant vaccines

against seasonal flu provided little protection. A study at the U.S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published in May 2009 found

that children had no preexisting immunity to the new strain but that

adults, particularly those older than 60, had some degree of immunity. Children showed no cross-reactive antibody reaction to the new strain, adults aged 18 to 60 had 6–9%, and older adults 33%.[62][63]

While it has been thought that these findings suggest the partial

immunity in older adults may be due to previous exposure to similar

seasonal influenza viruses, a November 2009 study of a rural

unvaccinated population in China found only a 0.3% cross-reactive

antibody reaction to the H1N1 strain, suggesting that previous

vaccinations for seasonal flu and not exposure may have resulted in the

immunity found in the older U.S. population.[64]It has been determined that the strain contains genes from five different flu viruses: North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza and two swine influenza viruses typically found in Asia and Europe. Further analysis has shown that several proteins of the virus are most similar to strains that cause mild symptoms in humans, leading virologist Wendy Barclay to suggest on 1 May 2009, that the initial indications are that the virus was unlikely to cause severe symptoms for most people.[65]

The virus is currently less lethal than previous pandemic strains and kills about 0.01–0.03% of those infected; the 1918 influenza was about one hundred times more lethal and had a case fatality rate of 2–3%.[66] By 14 November 2009, the virus had infected one in six Americans with 200,000 hospitalisations and 10,000 deaths – as many hospitalizations and fewer deaths than in an average flu season overall, but with much higher risk for those under 50. With deaths of 1,100 children and 7,500 adults 18 to 64, these figures "are much higher than in a usual flu season".[67]

In June 2010, scientists from Hong Kong reported discovery of a new swine flu virus which is a hybrid of the pandemic H1N1 virus and viruses previously found in pigs. It is the first report of a reassortment of the pandemic virus, which in humans has been slow to evolve. Nancy Cox, head of the influenza division at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has said, "This particular paper is extremely interesting because it demonstrates for the first time what we had worried about at the very onset of the pandemic, and that is that this particular virus, when introduced into pigs, could reassort with the resident viruses in pigs and we would have new gene constellations. And bingo, here we are." Pigs have been termed the mixing vessel of flu because they can be infected both by avian flu viruses, which rarely directly infect people, and by human viruses. When pigs become simultaneously infected with more than one virus, the viruses can swap genes, producing new variants which can pass to humans and sometimes spread amongst them.[68] "Unlike the situation with birds and humans, we have a situation with pigs and humans where there's a two-way street of exchange of viruses. With pigs it's very much a two-way street".[69]

Transmission

Spread of the H1N1 virus is thought to occur in the same way that seasonal flu spreads. Flu viruses are spread mainly from person to person through coughing or sneezing by people with influenza. Sometimes people may become infected by touching something – such as a surface or object – with flu viruses on it and then touching their face. "Avoid touching your eyes, nose or mouth. Germs spread this way".[12]The basic reproduction number (the average number of other individuals whom each infected individual will infect, in a population which has no immunity to the disease) for the 2009 novel H1N1 is estimated to be 1.75.[70] A December 2009 study found that the transmissibility of the H1N1 influenza virus in households is lower than that seen in past pandemics. Most transmissions occur soon before or after the onset of symptoms.[71]

The H1N1 virus has been transmitted to animals, including swine, turkeys, ferrets, household cats, at least one dog and a cheetah.[72][73][74][75]

Prevention

See also: Influenza prevention, 2009 flu pandemic vaccine, and Influenza vaccine#2009-2010 Northern Hemisphere winter season

The H1N1 vaccine was initially in short supply and in the U.S., the

CDC recommended that initial doses should go to priority groups such as

pregnant women, people who live with or care for babies under six months

old, children six months to four years old and health-care workers.[76]

In the UK, the NHS recommended vaccine priority go to people over six

months old who were clinically at risk for seasonal flu, pregnant women

and households of people with compromised immunity.[77]Although it was initially thought that two injections would be required, clinical trials showed that the new vaccine protected adults "with only one dose instead of two", and so the limited vaccine supplies would go twice as far as had been predicted.[78][79] Health officials worldwide were also concerned because the virus was new and could easily mutate and become more virulent, even though most flu symptoms were mild and lasted only a few days without treatment. Officials also urged communities, businesses and individuals to make contingency plans for possible school closures, multiple employee absences for illness, surges of patients in hospitals and other effects of potentially widespread outbreaks.[80]

In February 2010, the CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted for "universal" flu vaccination in the U.S. to include all people over six months of age. The 2010–2011 vaccine will protect against the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus and two other flu viruses.[81]

Public health response

See also: 2009 flu pandemic by country

U.S. officials observed that six years of concern about H5N1 avian flu did much to prepare for the current H1N1 flu outbreak, noting that after H5N1 emerged in Asia, ultimately killing about 60% of the few hundred people infected by it over the years, many countries took steps to try to prevent any similar crisis from spreading further.[85] The CDC and other U.S. governmental agencies[86] used the summer lull to take stock of the United States' response to H1N1 flu and attempt to patch any gaps in the public health safety net before flu season started in early autumn.[87] Preparations included planning a second influenza vaccination program in addition to that for seasonal influenza, and improving coordination between federal, state and local governments and private health providers.[87] On 24 October 2009, U.S. President Obama declared swine flu a national emergency, giving Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius authority to grant waivers to requesting hospitals from usual federal requirements.[88]

Vaccines

Main article: 2009 flu pandemic vaccine

U.S. President Barack Obama being vaccinated against H1N1 flu on 20 December 2009.

There are safety concerns for people who are allergic to eggs because the viruses for the vaccine are grown in chicken-egg-based cultures. People with egg allergies may be able to receive the vaccine, after consultation with their physician, in graded doses in a careful and controlled environment.[96] A vaccine manufactured by Baxter is made without using eggs, but requires two doses three weeks apart to produce immunity.[97]

As of late November 2009, in Canada there had been 24 confirmed cases of anaphylactic shock following vaccination, including one death. The estimated rate is one anaphylactic reaction per 312,000 persons receiving the vaccine; however, six persons had suffered anaphylaxis out of 157,000 doses given from one batch of vaccine. Dr. David Butler-Jones, Canada's chief public health officer, stated that even though this was an adjuvanted vaccine, that did not appear to be the cause of this severe allergic reaction in these six patients.[98][99]

A CDC study released 28 Jan 2013, estimated that the Pandemic H1N1 vaccine saved roughly 300 lives and prevented about 1 million illnesses. The study concluded that had the vaccination program started 2 weeks earlier, close to 60% more cases could have been prevented.[100]

No comments:

Post a Comment