http://www.theguardian.com/us

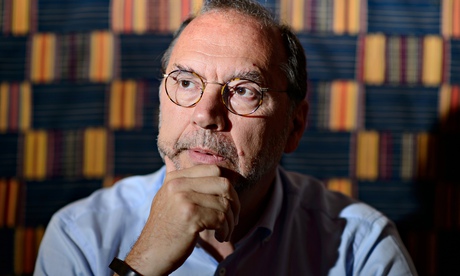

Peter

Piot was a researcher at a lab in Antwerp when a pilot brought him a

blood sample from a Belgian nun who had fallen mysteriously ill in Zaire

Professor Peter Piot,

the Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine:

‘Around June it became clear to me there was something different about

this outbreak. I began to get really worried’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP

Professor Piot, as a young scientist in Antwerp, you were part of the team that discovered the Ebola virus in 1976. How did it happen?

I still remember exactly. One day in September, a pilot from Sabena Airlines brought us a shiny blue Thermos and a letter from a doctor in Kinshasa in what was then Zaire. In the Thermos, he wrote, there was a blood sample from a Belgian nun who had recently fallen ill from a mysterious sickness in Yambuku, a remote village in the northern part of the country. He asked us to test the sample for yellow fever.

These days, Ebola may only be researched in high-security laboratories. How did you protect yourself back then?

We had no idea how dangerous the virus was. And there were no high-security labs in Belgium. We just wore our white lab coats and protective gloves. When we opened the Thermos, the ice inside had largely melted and one of the vials had broken. Blood and glass shards were floating in the ice water. We fished the other, intact, test tube out of the slop and began examining the blood for pathogens, using the methods that were standard at the time.

But the yellow fever virus apparently had nothing to do with the nun's illness.

No. And the tests for Lassa fever and typhoid were also negative. What, then, could it be? Our hopes were dependent on being able to isolate the virus from the sample. To do so, we injected it into mice and other lab animals. At first nothing happened for several days. We thought that perhaps the pathogen had been damaged from insufficient refrigeration in the Thermos. But then one animal after the next began to die. We began to realise that the sample contained something quite deadly.

But you continued?

Other samples from the nun, who had since died, arrived from Kinshasa. When we were just about able to begin examining the virus under an electron microscope, the World Health Organisation instructed us to send all of our samples to a high-security lab in England. But my boss at the time wanted to bring our work to conclusion no matter what. He grabbed a vial containing virus material to examine it, but his hand was shaking and he dropped it on a colleague's foot. The vial shattered. My only thought was: "Oh, shit!" We immediately disinfected everything, and luckily our colleague was wearing thick leather shoes. Nothing happened to any of us.

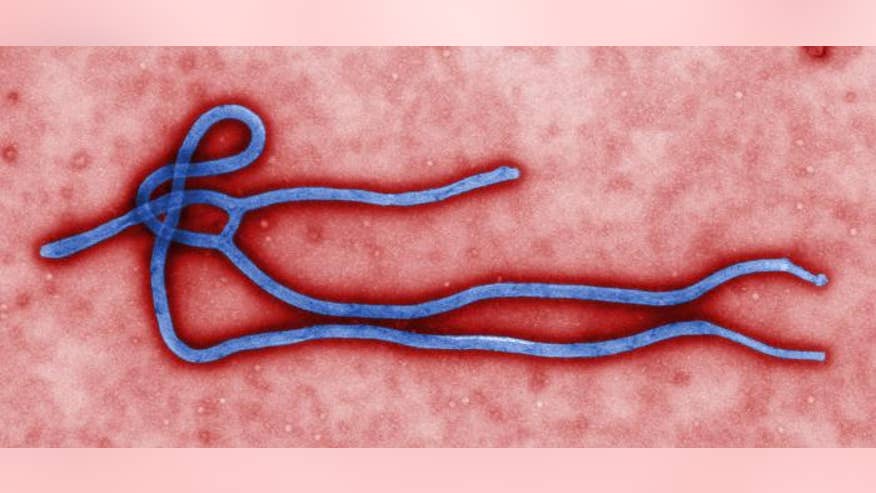

In the end, you were finally able to create an image of the virus using the electron microscope.

Yes, and our first thought was: "What the hell is that?" The virus that we had spent so much time searching for was very big, very long and worm-like. It had no similarities with yellow fever. Rather, it looked like the extremely dangerous Marburg virus which, like ebola, causes a haemorrhagic fever. In the 1960s the virus killed several laboratory workers in Marburg, Germany.

Were you afraid at that point?

I knew almost nothing about the Marburg virus at the time. When I tell my students about it today, they think I must come from the stone age. But I actually had to go the library and look it up in an atlas of virology. It was the American Centres for Disease Control which determined a short time later that it wasn't the Marburg virus, but a related, unknown virus. We had also learned in the meantime that hundreds of people had already succumbed to the virus in Yambuku and the area around it.

A few days later, you became one of the first scientists to fly to Zaire.

Yes. The nun who had died and her fellow sisters were all from Belgium. In Yambuku, which had been part of the Belgian Congo, they operated a small mission hospital. When the Belgian government decided to send someone, I volunteered immediately. I was 27 and felt a bit like my childhood hero, Tintin. And, I have to admit, I was intoxicated by the chance to track down something totally new.

I still remember exactly. One day in September, a pilot from Sabena Airlines brought us a shiny blue Thermos and a letter from a doctor in Kinshasa in what was then Zaire. In the Thermos, he wrote, there was a blood sample from a Belgian nun who had recently fallen ill from a mysterious sickness in Yambuku, a remote village in the northern part of the country. He asked us to test the sample for yellow fever.

These days, Ebola may only be researched in high-security laboratories. How did you protect yourself back then?

We had no idea how dangerous the virus was. And there were no high-security labs in Belgium. We just wore our white lab coats and protective gloves. When we opened the Thermos, the ice inside had largely melted and one of the vials had broken. Blood and glass shards were floating in the ice water. We fished the other, intact, test tube out of the slop and began examining the blood for pathogens, using the methods that were standard at the time.

But the yellow fever virus apparently had nothing to do with the nun's illness.

No. And the tests for Lassa fever and typhoid were also negative. What, then, could it be? Our hopes were dependent on being able to isolate the virus from the sample. To do so, we injected it into mice and other lab animals. At first nothing happened for several days. We thought that perhaps the pathogen had been damaged from insufficient refrigeration in the Thermos. But then one animal after the next began to die. We began to realise that the sample contained something quite deadly.

But you continued?

Other samples from the nun, who had since died, arrived from Kinshasa. When we were just about able to begin examining the virus under an electron microscope, the World Health Organisation instructed us to send all of our samples to a high-security lab in England. But my boss at the time wanted to bring our work to conclusion no matter what. He grabbed a vial containing virus material to examine it, but his hand was shaking and he dropped it on a colleague's foot. The vial shattered. My only thought was: "Oh, shit!" We immediately disinfected everything, and luckily our colleague was wearing thick leather shoes. Nothing happened to any of us.

In the end, you were finally able to create an image of the virus using the electron microscope.

Yes, and our first thought was: "What the hell is that?" The virus that we had spent so much time searching for was very big, very long and worm-like. It had no similarities with yellow fever. Rather, it looked like the extremely dangerous Marburg virus which, like ebola, causes a haemorrhagic fever. In the 1960s the virus killed several laboratory workers in Marburg, Germany.

Were you afraid at that point?

I knew almost nothing about the Marburg virus at the time. When I tell my students about it today, they think I must come from the stone age. But I actually had to go the library and look it up in an atlas of virology. It was the American Centres for Disease Control which determined a short time later that it wasn't the Marburg virus, but a related, unknown virus. We had also learned in the meantime that hundreds of people had already succumbed to the virus in Yambuku and the area around it.

A few days later, you became one of the first scientists to fly to Zaire.

Yes. The nun who had died and her fellow sisters were all from Belgium. In Yambuku, which had been part of the Belgian Congo, they operated a small mission hospital. When the Belgian government decided to send someone, I volunteered immediately. I was 27 and felt a bit like my childhood hero, Tintin. And, I have to admit, I was intoxicated by the chance to track down something totally new.

A girl is led to an ambulance after showing signs of Ebola infection

in the village of Freeman Reserve, 30 miles north of the Liberian

capital, Monrovia. Photograph: Jerome Delay/AP

Was there any room for fear, or at least worry?

Of course it was clear to us that we were dealing with one of the deadliest infectious diseases the world had ever seen – and we had no idea that it was transmitted via bodily fluids! It could also have been mosquitoes. We wore protective suits and latex gloves and I even borrowed a pair of motorcycle goggles to cover my eyes. But in the jungle heat it was impossible to use the gas masks that we bought in Kinshasa. Even so, the Ebola patients I treated were probably just as shocked by my appearance as they were about their intense suffering. I took blood from around 10 of these patients. I was most worried about accidentally poking myself with the needle and infecting myself that way.

But you apparently managed to avoid becoming infected.

Well, at some point I did actually develop a high fever, a headache and diarrhoea …

... similar to Ebola symptoms?

Exactly. I immediately thought: "Damn, this is it!" But then I tried to keep my cool. I knew the symptoms I had could be from something completely different and harmless. And it really would have been stupid to spend two weeks in the horrible isolation tent that had been set up for us scientists for the worst case. So I just stayed alone in my room and waited. Of course, I didn't get a wink of sleep, but luckily I began feeling better by the next day. It was just a gastrointestinal infection. Actually, that is the best thing that can happen in your life: you look death in the eye but survive. It changed my whole approach, my whole outlook on life at the time.

You were also the one who gave the virus its name. Why Ebola?

On that day our team sat together late into the night – we had also had a couple of drinks – discussing the question. We definitely didn't want to name the new pathogen "Yambuku virus", because that would have stigmatised the place forever. There was a map hanging on the wall and our American team leader suggested looking for the nearest river and giving the virus its name. It was the Ebola river. So by around three or four in the morning we had found a name. But the map was small and inexact. We only learned later that the nearest river was actually a different one. But Ebola is a nice name, isn't it?

In the end, you discovered that the Belgian nuns had unwittingly spread the virus. How did that happen?

In their hospital they regularly gave pregnant women vitamin injections using unsterilised needles. By doing so, they infected many young women in Yambuku with the virus. We told the nuns about the terrible mistake they had made, but looking back I would say that we were much too careful in our choice of words. Clinics that failed to observe this and other rules of hygiene functioned as catalysts in all additional Ebola outbreaks. They drastically sped up the spread of the virus or made the spread possible in the first place. Even in the current Ebola outbreak in west Africa, hospitals unfortunately played this ignominious role in the beginning.

After Yambuku, you spent the next 30 years of your professional life devoted to combating Aids. But now Ebola has caught up to you again. American scientists fear that hundreds of thousands of people could ultimately become infected. Was such an epidemic to be expected?

No, not at all. On the contrary, I always thought that Ebola, in comparison to Aids or malaria, didn't present much of a problem because the outbreaks were always brief and local. Around June it became clear to me that there was something fundamentally different about this outbreak. At about the same time, the aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières sounded the alarm. We Flemish tend to be rather unemotional, but it was at that point that I began to get really worried.

Why did WHO react so late?

On the one hand, it was because their African regional office isn't staffed with the most capable people but with political appointees. And the headquarters in Geneva suffered large budget cuts that had been agreed to by member states. The department for haemorrhagic fever and the one responsible for the management of epidemic emergencies were hit hard. But since August WHO has regained a leadership role.

There is actually a well-established procedure for curtailing Ebola outbreaks: isolating those infected and closely monitoring those who had contact with them. How could a catastrophe such as the one we are now seeing even happen?

I think it is what people call a perfect storm: when every individual circumstance is a bit worse than normal and they then combine to create a disaster. And with this epidemic there were many factors that were disadvantageous from the very beginning. Some of the countries involved were just emerging from terrible civil wars, many of their doctors had fled and their healthcare systems had collapsed. In all of Liberia, for example, there were only 51 doctors in 2010, and many of them have since died of Ebola.

The fact that the outbreak began in the densely populated border region between Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia ...

… also contributed to the catastrophe. Because the people there are extremely mobile, it was much more difficult than usual to track down those who had had contact with the infected people. Because the dead in this region are traditionally buried in the towns and villages they were born in, there were highly contagious Ebola corpses travelling back and forth across the borders in pickups and taxis. The result was that the epidemic kept flaring up in different places.

For the first time in its history, the virus also reached metropolises such as Monrovia and Freetown. Is that the worst thing that can happen?

In large cities – particularly in chaotic slums – it is virtually impossible to find those who had contact with patients, no matter how great the effort. That is why I am so worried about Nigeria as well. The country is home to mega-cities like Lagos and Port Harcourt, and if the Ebola virus lodges there and begins to spread, it would be an unimaginable catastrophe.

Have we completely lost control of the epidemic?

I have always been an optimist and I think that we now have no other choice than to try everything, really everything. It's good that the United States and some other countries are finally beginning to help. But Germany or even Belgium, for example, must do a lot more. And it should be clear to all of us: This isn't just an epidemic any more. This is a humanitarian catastrophe. We don't just need care personnel, but also logistics experts, trucks, jeeps and foodstuffs. Such an epidemic can destabilise entire regions. I can only hope that we will be able to get it under control. I really never thought that it could get this bad.

What can really be done in a situation when anyone can become infected on the streets and, like in Monrovia, even the taxis are contaminated?

We urgently need to come up with new strategies. Currently, helpers are no longer able to care for all the patients in treatment centres. So caregivers need to teach family members who are providing care to patients how to protect themselves from infection to the extent possible. This on-site educational work is currently the greatest challenge. Sierra Leone experimented with a three-day curfew in an attempt to at least flatten out the infection curve a bit. At first I thought: "That is totally crazy." But now I wonder, "why not?" At least, as long as these measures aren't imposed with military power.

A three-day curfew sounds a bit desperate.

Yes, it is rather medieval. But what can you do? Even in 2014, we hardly have any way to combat this virus.

Do you think we might be facing the beginnings of a pandemic?

There will certainly be Ebola patients from Africa who come to us in the hopes of receiving treatment. And they might even infect a few people here who may then die. But an outbreak in Europe or North America would quickly be brought under control. I am more worried about the many people from India who work in trade or industry in west Africa. It would only take one of them to become infected, travel to India to visit relatives during the virus's incubation period, and then, once he becomes sick, go to a public hospital there. Doctors and nurses in India, too, often don't wear protective gloves. They would immediately become infected and spread the virus.

The virus is continually changing its genetic makeup. The more people who become infected, the greater the chance becomes that it will mutate ...

... which might speed its spread. Yes, that really is the apocalyptic scenario. Humans are actually just an accidental host for the virus, and not a good one. From the perspective of a virus, it isn't desirable for its host, within which the pathogen hopes to multiply, to die so quickly. It would be much better for the virus to allow us to stay alive longer.

Could the virus suddenly change itself such that it could be spread through the air?

Like measles, you mean? Luckily that is extremely unlikely. But a mutation that would allow Ebola patients to live a couple of weeks longer is certainly possible and would be advantageous for the virus. But that would allow Ebola patients to infect many, many more people than is currently the case.

But that is just speculation, isn't it?

Certainly. But it is just one of many possible ways the virus could change to spread itself more easily. And it is clear that the virus is mutating.

You and two colleagues wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal supporting the testing of experimental drugs. Do you think that could be the solution?

Patients could probably be treated most quickly with blood serum from Ebola survivors, even if that would likely be extremely difficult given the chaotic local conditions. We need to find out now if these methods, or if experimental drugs like ZMapp, really help. But we should definitely not rely entirely on new treatments. For most people, they will come too late in this epidemic. But if they help, they should be made available for the next outbreak.

Testing of two vaccines is also beginning. It will take a while, of course, but could it be that only a vaccine can stop the epidemic?

I hope that's not the case. But who knows? Maybe.

In Zaire during that first outbreak, a hospital with poor hygiene was responsible for spreading the illness. Today almost the same thing is happening. Was Louis Pasteur right when he said: "It is the microbes who will have the last word"?

Of course, we are a long way away from declaring victory over bacteria and viruses. HIV is still here; in London alone, five gay men become infected daily. An increasing number of bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics. And I can still see the Ebola patients in Yambuku, how they died in their shacks and we couldn't do anything except let them die. In principle, it's still the same today. That is very depressing. But it also provides me with a strong motivation to do something. I love life. That is why I am doing everything I can to convince the powerful in this world to finally send sufficient help to west Africa. Now!

Der Spiegel

Of course it was clear to us that we were dealing with one of the deadliest infectious diseases the world had ever seen – and we had no idea that it was transmitted via bodily fluids! It could also have been mosquitoes. We wore protective suits and latex gloves and I even borrowed a pair of motorcycle goggles to cover my eyes. But in the jungle heat it was impossible to use the gas masks that we bought in Kinshasa. Even so, the Ebola patients I treated were probably just as shocked by my appearance as they were about their intense suffering. I took blood from around 10 of these patients. I was most worried about accidentally poking myself with the needle and infecting myself that way.

But you apparently managed to avoid becoming infected.

Well, at some point I did actually develop a high fever, a headache and diarrhoea …

... similar to Ebola symptoms?

Exactly. I immediately thought: "Damn, this is it!" But then I tried to keep my cool. I knew the symptoms I had could be from something completely different and harmless. And it really would have been stupid to spend two weeks in the horrible isolation tent that had been set up for us scientists for the worst case. So I just stayed alone in my room and waited. Of course, I didn't get a wink of sleep, but luckily I began feeling better by the next day. It was just a gastrointestinal infection. Actually, that is the best thing that can happen in your life: you look death in the eye but survive. It changed my whole approach, my whole outlook on life at the time.

You were also the one who gave the virus its name. Why Ebola?

On that day our team sat together late into the night – we had also had a couple of drinks – discussing the question. We definitely didn't want to name the new pathogen "Yambuku virus", because that would have stigmatised the place forever. There was a map hanging on the wall and our American team leader suggested looking for the nearest river and giving the virus its name. It was the Ebola river. So by around three or four in the morning we had found a name. But the map was small and inexact. We only learned later that the nearest river was actually a different one. But Ebola is a nice name, isn't it?

In the end, you discovered that the Belgian nuns had unwittingly spread the virus. How did that happen?

In their hospital they regularly gave pregnant women vitamin injections using unsterilised needles. By doing so, they infected many young women in Yambuku with the virus. We told the nuns about the terrible mistake they had made, but looking back I would say that we were much too careful in our choice of words. Clinics that failed to observe this and other rules of hygiene functioned as catalysts in all additional Ebola outbreaks. They drastically sped up the spread of the virus or made the spread possible in the first place. Even in the current Ebola outbreak in west Africa, hospitals unfortunately played this ignominious role in the beginning.

After Yambuku, you spent the next 30 years of your professional life devoted to combating Aids. But now Ebola has caught up to you again. American scientists fear that hundreds of thousands of people could ultimately become infected. Was such an epidemic to be expected?

No, not at all. On the contrary, I always thought that Ebola, in comparison to Aids or malaria, didn't present much of a problem because the outbreaks were always brief and local. Around June it became clear to me that there was something fundamentally different about this outbreak. At about the same time, the aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières sounded the alarm. We Flemish tend to be rather unemotional, but it was at that point that I began to get really worried.

Why did WHO react so late?

On the one hand, it was because their African regional office isn't staffed with the most capable people but with political appointees. And the headquarters in Geneva suffered large budget cuts that had been agreed to by member states. The department for haemorrhagic fever and the one responsible for the management of epidemic emergencies were hit hard. But since August WHO has regained a leadership role.

There is actually a well-established procedure for curtailing Ebola outbreaks: isolating those infected and closely monitoring those who had contact with them. How could a catastrophe such as the one we are now seeing even happen?

I think it is what people call a perfect storm: when every individual circumstance is a bit worse than normal and they then combine to create a disaster. And with this epidemic there were many factors that were disadvantageous from the very beginning. Some of the countries involved were just emerging from terrible civil wars, many of their doctors had fled and their healthcare systems had collapsed. In all of Liberia, for example, there were only 51 doctors in 2010, and many of them have since died of Ebola.

The fact that the outbreak began in the densely populated border region between Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia ...

… also contributed to the catastrophe. Because the people there are extremely mobile, it was much more difficult than usual to track down those who had had contact with the infected people. Because the dead in this region are traditionally buried in the towns and villages they were born in, there were highly contagious Ebola corpses travelling back and forth across the borders in pickups and taxis. The result was that the epidemic kept flaring up in different places.

For the first time in its history, the virus also reached metropolises such as Monrovia and Freetown. Is that the worst thing that can happen?

In large cities – particularly in chaotic slums – it is virtually impossible to find those who had contact with patients, no matter how great the effort. That is why I am so worried about Nigeria as well. The country is home to mega-cities like Lagos and Port Harcourt, and if the Ebola virus lodges there and begins to spread, it would be an unimaginable catastrophe.

Have we completely lost control of the epidemic?

I have always been an optimist and I think that we now have no other choice than to try everything, really everything. It's good that the United States and some other countries are finally beginning to help. But Germany or even Belgium, for example, must do a lot more. And it should be clear to all of us: This isn't just an epidemic any more. This is a humanitarian catastrophe. We don't just need care personnel, but also logistics experts, trucks, jeeps and foodstuffs. Such an epidemic can destabilise entire regions. I can only hope that we will be able to get it under control. I really never thought that it could get this bad.

What can really be done in a situation when anyone can become infected on the streets and, like in Monrovia, even the taxis are contaminated?

We urgently need to come up with new strategies. Currently, helpers are no longer able to care for all the patients in treatment centres. So caregivers need to teach family members who are providing care to patients how to protect themselves from infection to the extent possible. This on-site educational work is currently the greatest challenge. Sierra Leone experimented with a three-day curfew in an attempt to at least flatten out the infection curve a bit. At first I thought: "That is totally crazy." But now I wonder, "why not?" At least, as long as these measures aren't imposed with military power.

A three-day curfew sounds a bit desperate.

Yes, it is rather medieval. But what can you do? Even in 2014, we hardly have any way to combat this virus.

Do you think we might be facing the beginnings of a pandemic?

There will certainly be Ebola patients from Africa who come to us in the hopes of receiving treatment. And they might even infect a few people here who may then die. But an outbreak in Europe or North America would quickly be brought under control. I am more worried about the many people from India who work in trade or industry in west Africa. It would only take one of them to become infected, travel to India to visit relatives during the virus's incubation period, and then, once he becomes sick, go to a public hospital there. Doctors and nurses in India, too, often don't wear protective gloves. They would immediately become infected and spread the virus.

The virus is continually changing its genetic makeup. The more people who become infected, the greater the chance becomes that it will mutate ...

... which might speed its spread. Yes, that really is the apocalyptic scenario. Humans are actually just an accidental host for the virus, and not a good one. From the perspective of a virus, it isn't desirable for its host, within which the pathogen hopes to multiply, to die so quickly. It would be much better for the virus to allow us to stay alive longer.

Could the virus suddenly change itself such that it could be spread through the air?

Like measles, you mean? Luckily that is extremely unlikely. But a mutation that would allow Ebola patients to live a couple of weeks longer is certainly possible and would be advantageous for the virus. But that would allow Ebola patients to infect many, many more people than is currently the case.

But that is just speculation, isn't it?

Certainly. But it is just one of many possible ways the virus could change to spread itself more easily. And it is clear that the virus is mutating.

You and two colleagues wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal supporting the testing of experimental drugs. Do you think that could be the solution?

Patients could probably be treated most quickly with blood serum from Ebola survivors, even if that would likely be extremely difficult given the chaotic local conditions. We need to find out now if these methods, or if experimental drugs like ZMapp, really help. But we should definitely not rely entirely on new treatments. For most people, they will come too late in this epidemic. But if they help, they should be made available for the next outbreak.

Testing of two vaccines is also beginning. It will take a while, of course, but could it be that only a vaccine can stop the epidemic?

I hope that's not the case. But who knows? Maybe.

In Zaire during that first outbreak, a hospital with poor hygiene was responsible for spreading the illness. Today almost the same thing is happening. Was Louis Pasteur right when he said: "It is the microbes who will have the last word"?

Of course, we are a long way away from declaring victory over bacteria and viruses. HIV is still here; in London alone, five gay men become infected daily. An increasing number of bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics. And I can still see the Ebola patients in Yambuku, how they died in their shacks and we couldn't do anything except let them die. In principle, it's still the same today. That is very depressing. But it also provides me with a strong motivation to do something. I love life. That is why I am doing everything I can to convince the powerful in this world to finally send sufficient help to west Africa. Now!

Der Spiegel