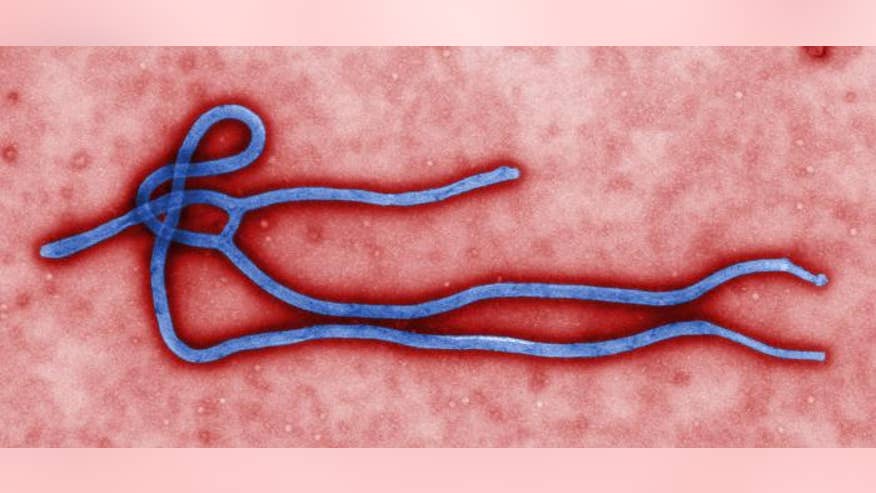

Scanning electron micrograph of an HIV-infected H9 T cell. Credit: NIAID

http://medicalxpress.com/

The HIV pandemic with us today is almost certain to have begun its global spread from Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), according to a new study.

An international team, led by Oxford University and University of Leuven scientists, has reconstructed the genetic history of the HIV-1 group M pandemic, the event that saw HIV spread across the African continent and around the world, and concluded that it originated in Kinshasa. The team's analysis suggests that the common ancestor of group M is highly likely to have emerged in Kinshasa around 1920 (with 95% of estimated dates between 1909 and 1930).

HIV is known to have been transmitted from primates and apes to humans at least 13 times but only one of these transmission events has led to a human pandemic. It was only with the event that led to HIV-1 group M that a pandemic occurred, resulting in almost 75 million infections to date. The team's analysis suggests that, between the 1920s and 1950s, a 'perfect storm' of factors, including urban growth, strong railway links during Belgian colonial rule, and changes to the sex trade, combined to see HIV emerge from Kinshasa and spread across the globe.

A report of the research is published in this week's Science.

'Until now most studies have taken a piecemeal approach to HIV's genetic history, looking at particular HIV genomes in particular locations,' said Professor Oliver Pybus of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, a senior author of the paper. 'For the first time we have analysed all the available evidence using the latest phylogeographic techniques, which enable us to statistically estimate where a virus comes from. This means we can say with a high degree of certainty where and when the HIV pandemic originated. It seems a combination of factors in Kinshasa in the early 20th Century created a 'perfect storm' for the emergence of HIV, leading to a generalised epidemic with unstoppable momentum that unrolled across sub-Saharan Africa.'

'Our study required the development of a statistical framework for reconstructing the spread of viruses through space and time from their genome sequences,' said Professor Philippe Lemey of the University of Leuven's Rega Institute, another senior author of the paper. 'Once the pandemic's spatiotemporal origins were clear they could be compared with historical data and it became evident that the early spread of HIV-1 from Kinshasa to other population centres followed predictable patterns.'

One of the factors the team's analysis suggests was key to the HIV pandemic's origins was the DRC's transport links, in particular its railways, that made Kinshasa one of the best connected of all central African cities.

'Data from colonial archives tells us that by the end of 1940s over one million people were travelling through Kinshasa on the railways each year,' said Dr Nuno Faria of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, first author of the paper. 'Our genetic data tells us that HIV very quickly spread across the Democratic Republic of the Congo (a country the size of Western Europe), travelling with people along railways and waterways to reach Mbuji-Mayi and Lubumbashi in the extreme South and Kisangani in the far North by the end of the 1930s and early 1950s. This helped establishing early secondary foci of HIV-1 transmission in regions that were well connected to southern and eastern African countries. We think it is likely that the social changes around the independence in 1960 saw the virus 'break out' from small groups of infected people to infect the wider population and eventually the world.'

It had been suggested that demographic growth or genetic differences between HIV-1 group M and other strains might be major factors in the establishment of the HIV pandemic. However the team's evidence suggests that, alongside transport, social changes such as the changing behaviour of sex workers, and public health initiatives against other diseases that led to the unsafe use of needles may have contributed to turning HIV into a full-blown epidemic – supporting ideas originally put forward by study co-author Jacques Pepin from the Université de Sherbrooke, Canada.

Professor Oliver Pybus said: 'Our research suggests that following the original animal to human transmission of the virus (probably through the hunting or handling of bush meat) there was only a small 'window' during the Belgian colonial era for this particular strain of HIV to emerge and spread into a pandemic. By the 1960s transport systems, such as the railways, that enabled the virus to spread vast distances were less active, but by that time the seeds of the pandemic were already sown across Africa and beyond.'

The team says that more research is needed to understand the role different social factors may have played in the origins of the HIV pandemic; in particular research on archival specimens to study the origins and evolution of HIV, and research into the relationship between the spread of Hepatitis C and the use of unsafe needles as part of public health initiatives may give further insights into the conditions that helped HIV to spread so widely.

More information: The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations, Science, 2014. www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/… 1126/science.1256739