It is hard to imagine that it was only 34 years ago when the

first case of HIV was first documented in the United States. Shortly

after, the virus seemed to spread like wildfire, burning a path of

hysteria, frustration and sadness across the U.S. and throughout the

world. In a short period of time, and thanks to a series of political

blunders from the Reagan administration and many other political figures

across the nation, HIV went from hundreds to millions and became the

closest we have ever come to a modern plague.

Although there is

still no cure for the virus, this plague is now classified as a chronic

illness with those who are HIV positive living long and healthy lives.

So the obscene terror that lived in the hearts of every gay man in the

world merely three decades ago has all but been erased in the mines of

the millennial age. In its place now lives a vague but

often-impenetrable fear of those who carry HIV and a diluted sense of

safety based on the idea that the transmission of HIV is related to a

character flaw of promiscuity. This blind faith that the virus is

relinquished to "other" types of people has allowed for this disease to

continue affecting the millennial generation at staggering rates.

According to the

Center for Disease Control's National Progress Report

of 2013, an estimated 1.1 million people are living with HIV in the

United States with 50,000 more becoming infected each year. One out of

every six people living with the virus are unaware that they are

infected, thus continuing the cycle of transmission. And worse, one out

of every five gay men are living with HIV, yet the millennial generation

often treats the disease as if it is only reserved for the history

books.

But beyond the numbers, just what exactly does it mean to

live HIV in today's world? For starters, HIV is now officially

classified as a chronic disease. Although most people assume that

treatment involves a series of toxic cocktails that HIV positive men and

women take throughout the day, a person diagnosed today will most

likely be on one daily pill to manage the virus. And reports suggest

that, given a person is compliant with their medication; they can expect

the same estimated lifespan as they did when they were HIV negative.

"A

person who is 20-years-old and diagnosed today can expect to live into

their 70s, roughly the same lifespan they would expect prior to being

diagnosed," says Dr. Gary Blick, HIV Specialist and Founder of World

Health Clinicians, an international HIV treatment organization.

However,

it isn't all good news. The span of your life may be the same, but your

worries certainly are not. People living with the virus run an

increased risk of developing other life-threatening diseases such as

cancer, heart attack and stroke. Combined with other STI's, these risks

are even bigger, making it even more important for a person living with

HIV to manage all aspects of their health, not just their pillboxes.

However, an HIV positive diagnosis is merely a charge to be drastically

more responsible with a person's health instead of an order to make

arrangements for a pending funeral.

To many of the people living

with the disease, it is also a scarlet branding that induces emotional

and psychological symptoms that far outweigh the side effects listed on

the side of their medication bottles.

The organizations charged

with delivering the message of HIV awareness and prevention have

grappled with advancing their messaging with the advancements of modern

medicine. Managing HIV is a drastically different animal than it was

merely a decade ago, but many still view the virus with the same gravity

that they did in the 1990s. The few organizations who have tried to

modernize the approach to HIV education have been lambasted for "making

light" of the disease, trying to "make HIV cool," or downplaying the

severity of living with the virus.

This struggle over messaging

has never been more contentious then in the present as institutional

juggernauts like the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) battles with more

progressive activists and organizations over the promotion of PrEP, or

pre-exposure prophylaxis. This new drug, nicknamed the birth control

pill for HIV, now personifies the crux in HIV treatment debate.

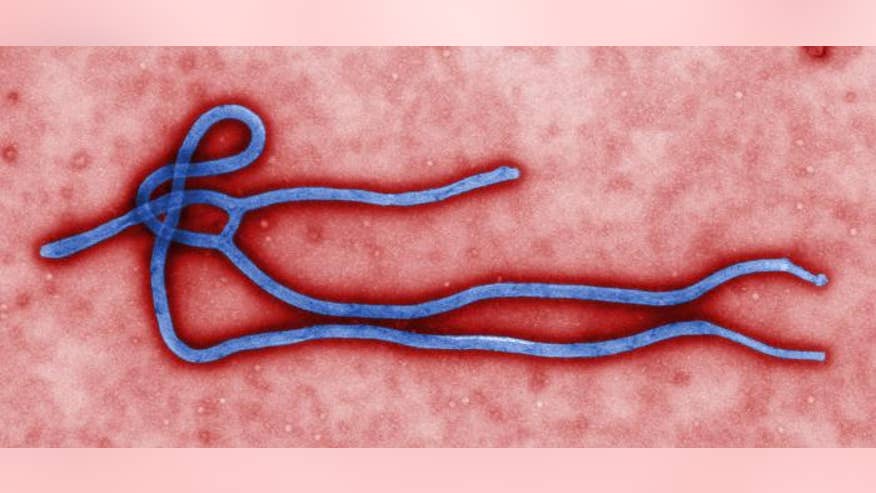

PrEP

is an Antiretroviral Therapy drug that, if taken correctly by an HIV

negative individual, has a 99 percent efficacy rate in preventing the

transmission of HIV from someone who is HIV positive. This drug has been

on the market since 2012, but several prominent organizations such as

AHF, the largest HIV treatment provider in the U.S., have taken an

active stance against the HIV prevention pill.

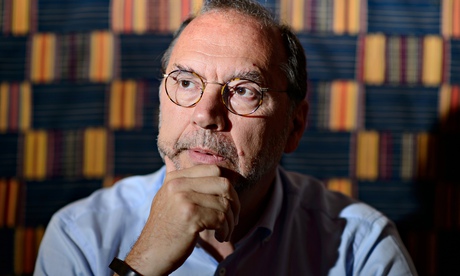

Michael Weinstein,

the Executive Director of AHF, has publicly referred to PrEP as a party

drug and suggested that the "people who would be taking the drug" could

not be trusted to be compliant with their dosage. This stigmatizing

rhetoric, combined with the pharmaceutical company, Gilead's,

unwillingness to advertise the drug to at-risk populations, has led to a

virtual standstill in people seeking a prescription for the prevention

pill.

People like J Nick Shirley, a 24-year-old gay man from

Dallas, represent the most at risk demographics for HIV transmission,

and yet has never heard of PrEP. When asked about the new form of

prevention, he was shocked that this was the first time he was hearing

about it.

"I just can't believe that we have such a

ground-breaking tool at our disposal and so many people don't know about

[PrEP]," Shirley said. "I am pretty sure none of my friends know about

it. We have never talked about it before."

Long term HIV survivor,

activist and former reality T.V star, Jack Mackenroth, is mortified

that organizations like AHF have taken on such a damaging approach to

PrEP.

"If this were the '90s, people would be lining up down the

streets to take PrEP," says Mackenroth. "It is so sad that the fear that

we went through has given way to the judgment and stigma from gay men

onto other gay men. HIV isn't going anywhere if we don't wake up and

realize that condom-only messages don't work."

Which leads us to

the use of the problem; organizations using worn out methods of

education and prevention, further stigmatizing others looking for

prevention methods beyond condoms and leaving the vast majority of

millennial, at-risk individuals to believe that HIV is a virus that

"other" people get.

Movies like

The Normal Heart serve

as history lessons, leading young gay men to cry, "Never forget," while

failing to realize the dangers they face. LGBT youth are left grappling

for connection, because most of the visible reminders of the risk of HIV

are only ashes, while the living, more relevant examples prefer to

remain in silence for fear of public ridicule and castigation. Sadly,

the community that was once unified under the call to fight the virus is

now complacent in a pseudo-class system of HIV status that only serves

to perpetuate transmission.

But change is on the horizon.

Grassroots campaigns such as HIV Equal, The Stigma Project, The Needle

Prick and several others have worked to change the climate of HIV stigma

for those living with the virus and educate the public on the real vs.

perceived danger of HIV transmission. A new wave of young, HIV positive

faces, such as Josh Robbins, Cory Lee Frederick and Jake Forth are

making their presence known in the public eye, humanizing the virus for

the millennial generation while serving as living examples that HIV is

still an issue for their age group. And this year, as the Obama

Administration unveiled the HIV Care Continuum at the third annual

HIV/AIDS Strategy, President Obama's HIV prevention policy recognized

Antiretroviral treatment as a valid form of prevention, giving authority

to the fact that HIV positive men who achieve undetectable viral load

levels are actively preventing the spread of HIV.

While the level

of danger has waned over the past three decades, the threat of HIV

still remains. Unlike the generations first affected by the virus, the

millennial age is now armed a wealth of information and a variety of

prevention tools to change the course of HIV for good. And this young

generation should take note that these tools came at a very heavy cost.

If you have had sex even once since your last HIV test without a

condom, it is worth it educate yourself on PrEP and determine if it is

right for you. It only takes one time to transmit the virus, and it only

takes one pill a day to stop it. The millennial generation no longer

has to face a multitude of limitations when concerning HIV, so there is

no excuse to get tested, know your status and pick up the slack in the

fight against HIV. After all, most of the heavy lifting has already been

done.