From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

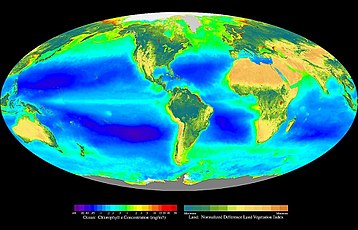

A false-color composite of global oceanic and terrestrial photoautotroph abundance, from September 1997 to August 2000. Provided by the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center and ORBIMAGE.[citation needed]

In a broader sense; biospheres are any closed, self-regulating systems containing ecosystems; including artificial ones such as Biosphere 2 and BIOS-3; and, potentially, ones on other planets or moons.[3]

Contents

Origin and use of the term

The term "biosphere" was coined by geologist Eduard Suess in 1875, which he defined as:[4]While this concept has a geological origin, it is an indication of the impact of both Charles Darwin and Matthew F. Maury on the Earth sciences. The biosphere's ecological context comes from the 1920s (see Vladimir I. Vernadsky), preceding the 1935 introduction of the term "ecosystem" by Sir Arthur Tansley (see ecology history). Vernadsky defined ecology as the science of the biosphere. It is an interdisciplinary concept for integrating astronomy, geophysics, meteorology, biogeography, evolution, geology, geochemistry, hydrology and, generally speaking, all life and Earth sciences."The place on Earth's surface where life dwells."

Narrow definition

The Second International Conference on Closed Life Systems defined biospherics as the science and technology of analogs and models of Earth's biosphere; i.e., artificial Earth-like biospheres. Others may include the creation of artificial non-Earth biospheres—for example, human-centered biospheres or a native Martian biosphere—in the field of biospherics.

Gaia hypothesis

In the early 1970s, the British chemist James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, a microbiologist from the United States, added to the hypothesis, specifically noting the ties between the biosphere and other Earth systems. For example, when carbon dioxide levels increase in the atmosphere, plants grow more quickly. As their growth continues, they remove more and more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.Many scientists are now involved in new fields of study that examine interactions between biotic and abiotic factors in the biosphere, such as geobiology and geomicrobiology.

Ecosystems occur when communities and their physical environment work together as a system. The difference between this and a biosphere is simple, the biosphere is everything in general terms.

Extent of Earth's biosphere

Every part of the planet, from the polar ice caps to the Equator, supports life of some kind. Recent advances in microbiology have demonstrated that microbes live deep beneath the Earth's terrestrial surface, and that the total mass of microbial life in so-called "uninhabitable zones" may, in biomass, exceed all animal and plant life on the surface. The actual thickness of the biosphere on earth is difficult to measure. Birds typically fly at altitudes of 650 to 1,800 metres, and fish that live deep underwater can be found down to -8,372 metres in the Puerto Rico Trench.[2]There are more extreme examples for life on the planet: Rüppell's vulture has been found at altitudes of 11,300 metres; bar-headed geese migrate at altitudes of at least 8,300 metres; yaks live at elevations between 3,200 to 5,400 metres above sea level; mountain goats live up to 3,050 metres. Herbivorous animals at these elevations depend on lichens, grasses, and herbs.

Microscopic organisms live at such extremes that, taking them into consideration, makes the thickness of the biosphere much greater. Culturable microbes have been found in the Earth's upper atmosphere as high as 41 km (25 mi) (Wainwright et al., 2003, in FEMS Microbiology Letters). It is unlikely, however, that microbes are active at such altitudes, where temperatures and air pressure are extremely low and ultraviolet radiation very high. More likely, these microbes were brought into the upper atmosphere by winds or possibly volcanic eruptions. Barophilic marine microbes have been found at more than 10 km (6 mi) depth in the Mariana Trench (Takamia et al., 1997, in FEMS Microbiology Letters). In fact, single-celled life forms have been found in the deepest part of the Mariana Trench, Challenger Deep, at depths of 36,201 feet (11,034 meters) [1]. Microbes are not limited to the air, water or the Earth's surface. Culturable thermophilic microbes have been extracted from cores drilled more than 5 km (3 mi) into the Earth's crust in Sweden (Gold, 1992, and Szewzyk, 1994, both in PNAS), from rocks between 65-75 °C.

Temperature increases with increasing depth into the Earth's crust. The speed at which the temperature increases depends on many factors, including type of crust (continental vs. oceanic), rock type, geographic location, etc. The upper known limit of temperature at which microbial life can exist is 122 °C (Methanopyrus kandleri Strain 116), and it is likely that the limit of life in the "deep biosphere" is defined by temperature rather than absolute depth.

Our biosphere is divided into a number of biomes, inhabited by broadly similar flora and fauna. On land, biomes are separated primarily by latitude. Terrestrial biomes lying within the Arctic and Antarctic Circles are relatively barren of plant and animal life, while most of the more populous biomes lie near the equator. Terrestrial organisms in temperate and Arctic biomes have relatively small amounts of total biomass, smaller energy budgets, and display prominent adaptations to cold, including world-spanning migrations, social adaptations, homeothermy, estivation and multiple layers of insulation.

Specific biospheres

When the word is followed by a number, it is usually referring to a specific system or number. Thus:- Biosphere 1, the planet Earth.

- Biosphere 2, laboratory in Arizona, United States, which contains 3.15 acres (13,000 m²) of closed ecosystem.

- BIOS-3, a closed ecosystem at the Institute of Biophysics in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, in what was then the Soviet Union.

- Biosphere J (CEEF, Closed Ecology Experiment Facilities), an experiment in Japan.[5][6]

Extraterrestrial biospheres

No biospheres have been detected beyond the Earth; therefore, the existence of extraterrestrial biospheres remains hypothetical. The rare Earth hypothesis suggests they should be very rare, save ones composed of microbial life only.[7] On the other hand, new research suggests that Earth analogs may be quite numerous, at least in the Milky Way galaxy.[8] Given limited understanding of abiogenesis, it is currently unknown what percentage of these planets actually develop biospheres.It is also possible that artificial biospheres will be created in the future, for example on Mars.[9]

No comments:

Post a Comment