From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Necrotizing fasciitis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Person with necrotizing fasciitis. The left leg shows extensive redness and necrosis.

|

|

Type I describes a polymicrobial infection, whereas Type II describes a monomicrobial infection. Many types of bacteria can cause necrotizing fasciitis (e.g., Group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, Aeromonas hydrophila[3]). Such infections are more likely to occur in people with compromised immune systems.[4]

Historically, group A streptococcus made up most cases of Type II infections. However, since as early as 2001, another serious form of monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis has been observed with increasing frequency,[5] caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Contents

Possible sources

Possible sources of MRSA may include eating undercooked contaminated meats,[6] working at municipal waste water treatment plants, exposure to secondary waste water spray irrigation,[7] consuming raw products produced from farm fields fertilized by human sewage sludge or septage, in hospital settings from patients of weakened immune systems,[8] or sharing/using dirty needles.[9]Signs and symptoms

Over 70% of cases are recorded in patients with at least one of the following clinical situations: immunosuppression, diabetes, alcoholism/drug abuse/smoking, malignancies, and chronic systemic diseases. For reasons that are unclear, it occasionally occurs in people with an apparently normal general condition.[10]The infection begins locally at a site of trauma, which may be severe (such as the result of surgery), minor, or even non-apparent. Patients usually complain of intense pain that may seem excessive given the external appearance of the skin. With progression of the disease, often within hours, tissue becomes swollen. Diarrhea and vomiting are also common symptoms.

In the early stages, signs of inflammation may not be apparent if the bacteria are deep within the tissue. If they are not deep, signs of inflammation, such as redness and swollen or hot skin, develop very quickly. Skin color may progress to violet, and blisters may form, with subsequent necrosis (death) of the subcutaneous tissues.

Furthermore, patients with necrotizing fasciitis typically have a fever and appear very ill. Mortality rates have been noted as high as 73 percent if left untreated.[11] Without surgery and medical assistance, such as antibiotics, the infection will rapidly progress and will eventually lead to death.[12]

Pathophysiology

Micrograph of necrotizing fasciitis, showing necrosis (center of image) of the dense connective tissue, i.e. fascia, interposed between fat lobules (top-right and bottom-left of image). H&E stain

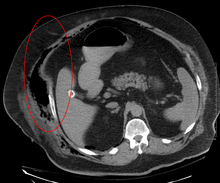

Diagnosis

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score can be utilized to risk stratify patients presenting with signs of cellulitis to determine the likelihood of necrotizing fasciitis being present. It uses six serologic measures: C-reactive protein, total white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine and glucose. A score greater than 6 indicates that necrotizing fasciitis should be seriously considered. The scoring criteria are as follows:- CRP (mg/L) ≥150: 4 points

- WBC count (×103/mm3)

- <15: 0 points

- 15–25: 1 point

- >25: 2 points

- Hemoglobin (g/dL)

- >13.5: 0 points

- 11–13.5: 1 point

- <11: 2 points

- Sodium (mmol/L) <135: 2 points

- Creatinine (umol/L) >141: 2 points

- Glucose (mmol/L) >10: 1 point[13][14]

Treatment

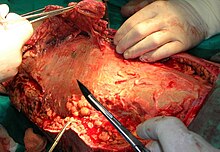

Patients are typically taken to surgery based on a high index of suspicion, determined by the patient's signs and symptoms. In necrotizing fasciitis, aggressive surgical debridement (removal of infected tissue) is always necessary to keep it from spreading and is the only treatment available. Diagnosis is confirmed by visual examination of the tissues and by tissue samples sent for microscopic evaluation.

As in other maladies characterized by massive wounds or tissue destruction, hyperbaric oxygen treatment can be a valuable adjunctive therapy but is not widely available.[15] Amputation of the affected limb(s) may be necessary. Repeat explorations usually need to be done to remove additional necrotic tissue. Typically, this leaves a large open wound, which often requires skin grafting, though necrosis of internal (thoracic and abdominal) viscera – such as intestinal tissue – are also possible. The associated systemic inflammatory response is usually profound, and most patients will require monitoring in an intensive care unit. Because of the extreme nature of many of these wounds and the grafting and debridement that accompanies such a treatment, a burn center's wound clinic, which has staff trained in such wounds, may be utilized.

Treatment for necrotizing fasciitis may involve an interdisciplinary care team. For example, in the case of a necrotizing fasciitis involving the head and neck, the team could include otolaryngologists, speech pathologists, intensivists, microbiologists and plastic surgeons or oral and maxillofacial surgeons.[16]

Notable cases

- 1994 Lucien Bouchard, former premier of Québec, Canada, who became infected in 1994 while leader of the federal official opposition Bloc Québécois party, lost a leg to the illness.[17]

- 1994 A cluster of cases occurred in Gloucestershire, in the west of England. Of five confirmed and one probable infections, two died. The cases were believed to be connected. The first two had acquired the Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria during surgery, the remaining four were community-acquired.[18] The cases generated much newspaper coverage, and lurid headlines such as "Flesh Eating Bug Ate My Face".[19]

- 1997 Ken Kendrick, former agent and partial owner of the San Diego Padres and Arizona Diamondbacks, contracted the disease in 1997. He had seven surgeries in a little more than a week but later recovered fully.[20]

- 2004 Eric Allin Cornell, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, lost his left arm and shoulder to the disease in 2004.[21]

- 2004 Jan Peter Balkenende, former Prime Minister of the Netherlands was infected in 2004. He was in the hospital for several weeks but recovered fully.[22]

- 2005 Alexandru Marin, an experimental particle physicist, professor at MIT, Boston University and Harvard University, and researcher at CERN and JINR, died from the disease.[23]

- 2006 David Walton, a leading economist in the UK and a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, died in June 2006 of the disease within 24 hours of diagnosis.[24]

- 2006 Alan Coren, British writer and satirist, announced in his Christmas 2006 column for The Times that his long absence as a columnist had been caused by his contracting the disease while on holiday in France.[25]

- 2009 R. W. Johnson, South African journalist and historian, contracted the disease in March 2009 after injuring his foot while swimming. His leg was amputated above the knee.[26]

- 2011 (January) Jeff Hanneman, guitarist for the thrash metal band Slayer, contracted the disease in 2011. He died of liver failure two years later, on May 2, 2013, and it was speculated his infection might be the cause of death. However, on May 9, 2013, the official cause of death was announced as alcohol-related cirrhosis. Hanneman and his family had apparently been unaware of the extent of the condition until shortly before his death.[27]

- 2011 (February) Peter Watts, Canadian science fiction author, contracted the disease in early 2011. On his blog, Watts reported, "I’m told I was a few hours away from being dead.... If there was ever a disease fit for a science fiction writer, flesh-eating disease has got to be it. This...spread across my leg as fast as a Star Trek space disease in time-lapse."[28]

- 2012 (May) Aimee Copeland, a 24-year old graduate student, contracted necrotizing fasciitis after she fell from a zip-line into the Little Tallapoosa River which caused a deep cut in her leg. Copeland’s entire leg was amputated along with her other limbs as a side effect of the disease and treatment.[29]

- 2012 (December) Mary Ryan from Florida – originally from Cork, Ireland – underwent liposuction on her abdomen, neck and jowls on December 19. After the procedure she complained about extreme nausea and pain in her abdomen, and because of this she failed to attend a scheduled post-op checkup. As she reported feeling better, she traveled to Ireland on December 24 to visit her family. However, she did not travel with the prescribed antibiotics due to a communication breakdown. On arrival at her son's home on December 26 she reported feeling very ill. After consulting a local GP, Mrs. Ryan was admitted to the Intensive Care department of Cork University Hospital the same evening. Despite surgical intervention and high doses of antibiotics she died on December 29, only ten days after the liposuction treatment. The coroner's verdict was 'death by medical misadventure'.[30]

- 2013 Rick Teal, New Zealand father of three, was at work when he noticed a nagging pain in his right leg. Within half an hour he had developed a limp. He was subsequently admitted to Wellington Hospital and, two days after the onset of symptoms, he gave doctors permission to amputate his leg. Teal eventually recovered without amputation but large areas of infected flesh between his knee and ankle had to be debrided. Necrotizing fasciitis is on rise in New Zealand.[31]

See also

- Mucormycosis, a rare fungal infection that can present like necrotizing fasciitis

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Fournier gangrene

No comments:

Post a Comment