Right now, a fight for survival is taking place in the West

African nations of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Ebola, one of the

most lethal diseases on the planet, is on a killing rampage. In Guinea,

303 people have died. In Sierra Leone, 99 have perished, and in Guinea,

65 lives have been claimed.

Within a few days, these figures will be higher. And the disease

appears to just be getting warmed up. Spread by contact with bodily

fluids, Ebola is flourishing in West Africa, and could be coming soon to

a place near you.

When the outbreak began in Guinea in April, the mortality rate was

higher than it is now. But the virus is still an extreme hazard, and

health workers must work in full bio-hazard suits in order to keep

themselves from being infected by the patients they are serving. The

protective suits are extremely hot in the sweltering West African

climate. They are like little mobile sauna units, slowly cooking the

doctors, nurses and aids working inside them.

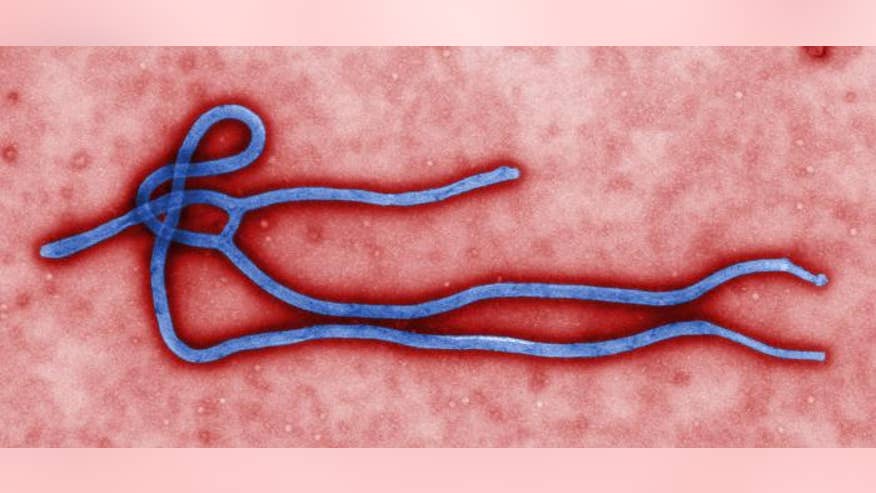

Named after the Ebola River, the virus was first discovered in 1976

in what was then Zaire and is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. A

viral disease, Ebola starts out like a bad flu, exhibiting initial

symptoms of fever, weakness, headache and muscle pain – but that’s where

the similarities end.

The more severe symptoms commence as early as two days after contact

with the virus. Ebola is a hemorrhagic fever, meaning it causes the

rupturing of blood vessels throughout the body. Victims may bleed from

the eyes, nose, mouth, ears, anus and genitals, as well as through skin

ruptures. The liver, lungs, spleen and lymph nodes can be overcome by

Ebola, leading to massive organ failure, and an agonizing death can

follow.

There are five strains of Ebola: Zaire, Sudan, Reston, Cote d’Ivoire,

and Bundibugyo. Of these, four are known to cause the disease in

humans, whereas Reston does not appear to do so. The disease is

transmitted from animals to humans. Fruit bats, monkeys, and wild game

may host the virus and spread it to humans, but bats in particular are

on the radar of health officials. They are known as reservoir species,

carrying the virus without becoming sick from the disease.

Despite urgent, high level attention from the World Health

Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ebola

has no specific treatment, no vaccine, and no effective medicines. Bed

rest and remaining hydrated appear to be as effective as any course of

treatment, with a disease whose mortality rate can be as high as 90

percent. In clinics, Ebola patients are kept isolated as much as

possible, and any utensils used to diagnose them must be fastidiously

sterilized. Health workers take a huge risk tending to the Ebola

infected, and only bio-hazard suits afford enough protection. Still,

even one accidental prick from a dirty needle can lead to infection. It

is very risky business.

Now, we don’t have to worry, right? Ebola is, after all, over in

Africa, far removed from us. Nothing could be further from the alarming

truth.

Imagine this scenario: A health worker tends to Ebola patients in

Guinea, and remains healthy due to good sanitation practices.

Eventually, that health worker needs to travel to the United States or

Europe, and he or she boards a plane. Unknowingly, they are infected but

symptom-free so far. On the long flight home, they start to feel some

aches and chills, and at one point, they sneeze, sending thousands of

viruses into the air through the atomized mucus expelled from the nose.

Other passengers breathe that air, taking in a few viruses here and

there, and they become infected.

And a global pandemic starts to roll.

This is neither a far-off scenario nor science fiction. It is a real

possibility. And this is why health officials are so gravely concerned

about the current Ebola outbreak. Unlike previous smaller outbreaks

which have occurred in rural locations, this one is happening in hot,

humid cities where crowds are dense and sanitation is sketchy; where

basic hygiene is often hard to manage and many people eat wild game that

might be infected. It is a perfect recipe for a massive, uncontrolled

outbreak. Infecting another person is as easy as a sneeze, a kiss,

cleaning up after someone, making contact with mucus, urine or feces.

The question, then, is what can you do? Except for staying away from

anyone infected, you can’t do much. Right now it’s up to the health

workers laboring in excessively hot bio-hazard suits, and to officials

who are working hard on containment. This situation in West Africa could

in fact be the start of a global disaster, or it may be another

near-miss. The threat is real, and the disease is on the move. Will we

dodge the Ebola bullet? Right now, all we can do is watch and wait.

Chris

Kilham is a medicine hunter who researches natural remedies all over

the world, from the Amazon to Siberia. He teaches ethnobotany at the

University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he is Explorer In Residence.

Chris advises herbal, cosmetic and pharmaceutical companies and is a

regular guest on radio and TV programs worldwide. His field research is

largely sponsored by Naturex of Avignon, France. Read more at MedicineHunter.com.