Pus is an

exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of

inflammation during

infection.

[1] An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an

abscess, whereas a visible collection of pus within or beneath the

epidermis is known as a

pustule or

pimple.

Pus consists of a thin,

protein-rich fluid, known as

liquor puris, and dead

leukocytes from the body's

immune response (mostly

neutrophils). During infection,

macrophages release

cytokines which trigger neutrophils to seek the site of infection by

chemotaxis. There, the neutrophils engulf and destroy the bacteria and the bacteria resist the immune response by releasing toxins called

leukocidins.

[2] As the neutrophils die off from toxins and old age, they are

destroyed by macrophages, forming the viscous pus.

Bacteria that cause pus are called

suppurative,

pyogenic,

[2][3] or

purulent. If the agent also creates

mucus, it is called

mucopurulent. Purulent infections can be treated with an

antiseptic.

Despite normally being of a whitish-yellow hue, changes in the color

of pus can be observed under certain circumstances. Pus is sometimes

green because of the presence of

myeloperoxidase,

an intensely green antibacterial protein produced by some types of

white blood cells. Green, foul-smelling pus is found in certain

infections of

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The greenish color is a result of the pyocyanin bacterial pigment it produces.

Amoebic abscesses of the

liver produce brownish pus, which is described as looking like "anchovy paste". Pus can also have a foul odor.

In almost all cases when there is a collection of pus in the body,

the clinician will try to create an opening for it to evacuate - this

principle has been distilled into the famous Latin aphorism "

Ubi pus, ibi evacua!"

Some common disease processes caused by pyogenic infections are

impetigo,

osteomyelitis,

septic arthritis, and

necrotizing fasciitis.

[4][not in citation given]

Pyogenic bacteria

A great many species of bacteria may be pyogenic. The most commonly found include:

[5][unreliable medical source?]

Exudate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An

exudate is any

fluid that filters from the

circulatory system into

lesions or areas of

inflammation. It can apply to plants as well as animals. Its composition varies but generally includes water and the dissolved

solutes of the main circulatory fluid such as sap or blood. In the case of blood it will contain some or all

plasma proteins,

white blood cells,

platelets, and in the case of local

vascular damage:

red blood cells.

In plants, it can be a healing and defensive response to repel insect

attack, or it can be an offensive habit to repel other incompatible or

competitive plants. Organisms that feed on exudate are known as

exudativores; for example, the

Vampire Bat exhibits

hematophagy, and the

Pygmy marmoset is an

obligate gummivore[1] (primarily eats tree gum).

In humans, exudate can be a pus-like or clear fluid. When an injury

occurs, leaving skin exposed, it leaks out of the blood vessels and into

nearby tissues. The fluid is composed of serum, fibrin, and white blood

cells. Exudate may ooze from cuts or from areas of infection or

inflammation.

[2]

Inflammation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Inflammation (

Latin,

īnflammō, "I ignite, set alight") is part of the complex biological response of

vascular tissues to harmful stimuli, such as

pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants.

[1]

The classical signs of acute inflammation are pain, heat, redness,

swelling, and loss of function. Inflammation is a protective attempt by

the organism to remove the injurious stimuli and to initiate the healing

process. Inflammation is not a synonym for

infection,

even in cases where inflammation is caused by infection. Although

infection is caused by a microorganism, inflammation is one of the

responses of the organism to the pathogen. However, inflammation is a

stereotyped response, and therefore it is considered as a mechanism of

innate immunity, as compared to

adaptive immunity, which is specific for each pathogen.

[2]

Progressive destruction of the tissue would compromise the survival

of the organism. However, chronic inflammation can also lead to a host

of diseases, such as

hay fever,

periodontitis,

atherosclerosis,

rheumatoid arthritis, and even cancer (e.g.,

gallbladder carcinoma). It is for that reason that inflammation is normally closely regulated by the body.

Inflammation can be classified as either

acute or

chronic.

Acute inflammation is the initial response of the body to harmful stimuli and is achieved by the increased movement of

plasma and

leukocytes (especially

granulocytes)

from the blood into the injured tissues. A cascade of biochemical

events propagates and matures the inflammatory response, involving the

local

vascular system, the

immune system, and various cells within the injured tissue. Prolonged inflammation, known as

chronic inflammation,

leads to a progressive shift in the type of cells present at the site

of inflammation and is characterized by simultaneous destruction and

healing of the tissue from the inflammatory process.

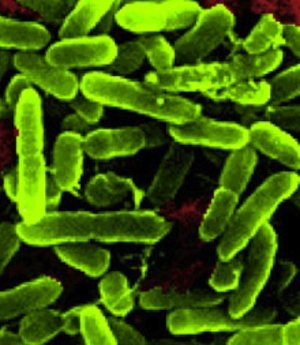

Staphylococcus aureus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Staphylococcus aureus is a

bacterium that is a member of the

Firmicutes, and is frequently found in the human respiratory tract and on the skin. Although

S. aureus is not always

pathogenic, it is a common cause of skin infections (e.g.

boils), respiratory disease (e.g.

sinusitis), and

food poisoning. Disease-associated strains often promote infections by producing potent protein

toxins, and expressing cell-surface proteins that

bind and inactivate antibodies. The emergence of

antibiotic-resistant forms of pathogenic

S. aureus (e.g.

MRSA) is a worldwide problem in clinical medicine.

Staphylococcus was first identified in

Aberdeen,

Scotland (1880) by the

surgeon Sir

Alexander Ogston in

pus from a surgical abscess in a knee joint.

[1] This name was later appended to

Staphylococcus aureus

by Rosenbach who was credited by the official system of nomenclature at

the time. It is estimated that 20% of the human population are

long-term carriers of

S. aureus[2] which can be found as part of the normal

skin flora and in anterior nares of the nasal passages.

[2][3] S. aureus is the most common species of staphylococcus to cause

Staph infections and is a successful pathogen due to a combination of nasal carriage and bacterial immuno-evasive strategies.

[2][3] S. aureus can cause a range of illnesses, from minor skin

infections, such as

pimples,

impetigo,

boils (furuncles),

cellulitis folliculitis,

carbuncles,

scalded skin syndrome, and

abscesses, to life-threatening diseases such as

pneumonia,

meningitis,

osteomyelitis,

endocarditis,

toxic shock syndrome (TSS),

bacteremia, and

sepsis. Its incidence ranges from skin, soft tissue, respiratory, bone, joint, endovascular to

wound infections. It is still one of the five most common causes of

nosocomial infections

and is often the cause of postsurgical wound infections. Each year,

some 500,000 patients in American hospitals contract a staphylococcal

infection.

[4]

Dawn Hepp shows off the wounds on her neck. (Courtesy Dawn

Dawn Hepp shows off the wounds on her neck. (Courtesy Dawn